The Vasquez Peak Wilderness is Colorado’s newest Wilderness protected by order of Congress using the Wilderness Protection Act of 1964. Established in 1993 the Wilderness Area encompasses 19.22 miles squared, or nearly 12,300 acres of pristine forest. The entirety of the Wilderness Area sits above 10,000 feet, and encompasses 15 miles of maintained trails making the hiking here a grueling experience for those not acclimatized to the altitude.

The 3,100 mile long Continental Divide Trail runs through the Vasquez Peaks Wilderness and offers routes to the eponymous Vasquez Peak and Vasquez Pass.

I came to the wilderness with the idea that I would climb Vasquez Peak, a hike that takes about 5 hours and 7 miles to complete. But in terms of elevation it’s no slouch, clocking in at nearly 3,000 feet of elevation change during the course of that hike. It’s steep, nearly as steep as some 14er hikes in the area. That’s part of the appeal though. Wilderness Areas tend to see far less traffic than other more popular spots, and they’re less littered with the Snickers wrappers of hikers gone by.

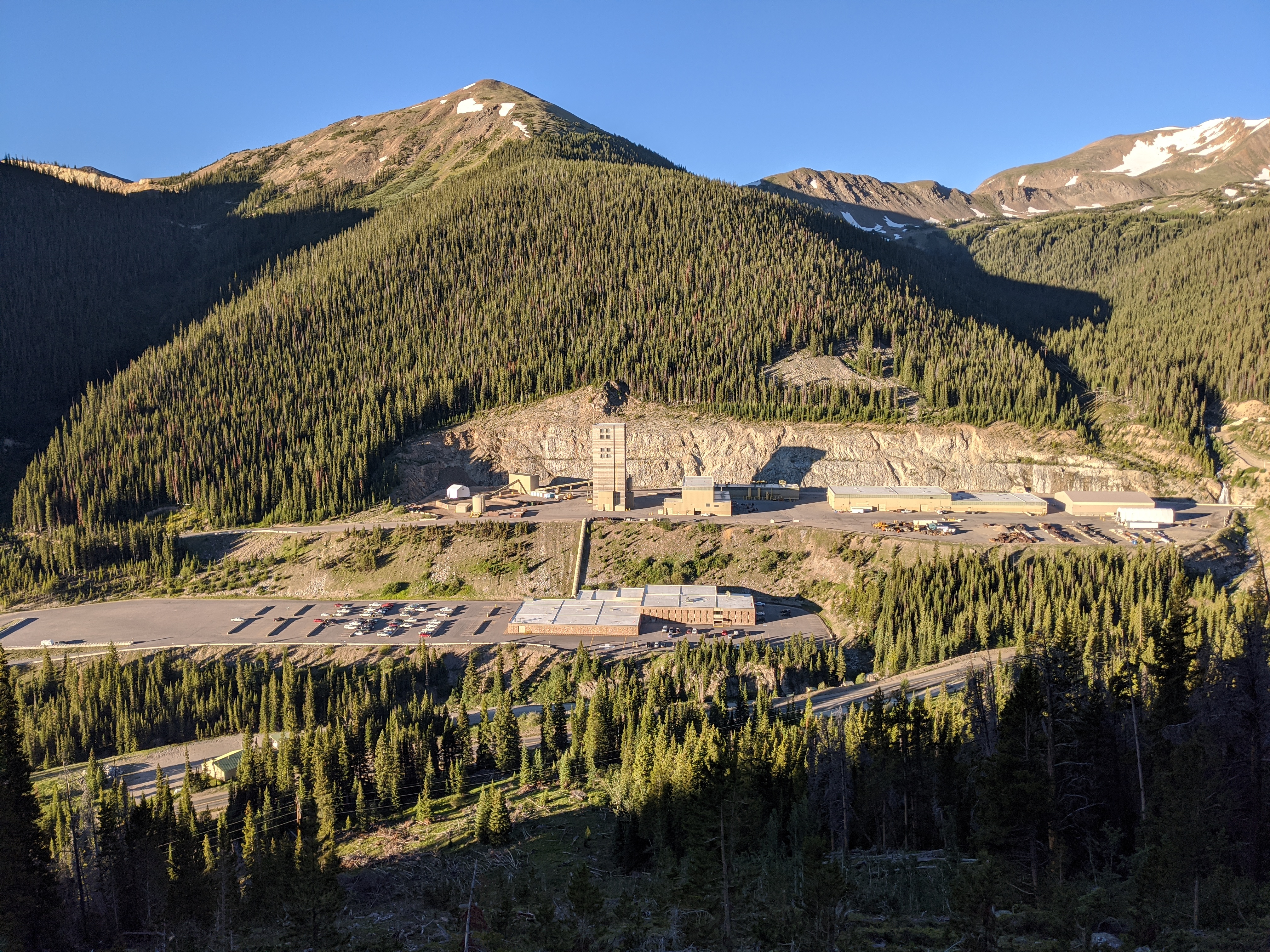

Driving into the trailhead around 7 in the morning I was greeted by a man in a full bomb suit waving me on to Jones Pass Road that the mine entrance splits off of. That was a little different, but it has to be explained that in the valley where the parking lot for the trailhead is — is also the Henderson Mine. I imagine he was preparing charges for the day, but I knew better to stick around and chat with a gentleman in full bomb gear.

The trailhead is wide enough for perhaps two dozen cars and Jones Pass Road continues on to the top. I initially parked in the dirt lot maintained by the Henderson Mine and walked to the Jones Pass sign. A clear trail marked it’s way up the mountain.

Mistakes Were Made

The first, and least obvious mistake I made at the time, was not realizing there are in fact two trailheads at this parking lot. One for a trail that goes up to Jones Pass, the other is for the Continental Divide Trail which takes you up to the Nystrom Trail required to both Summit Vasquez Peak as well as go to Vasquez Pass.

Going up the trail you quickly see a cabin and the remnants of two spring beds and some camp accouterments. No idea how long the cabin had been there, but there was a ceramic mug, less handle, buried deep in the soil surrounding the cabin. Blue and green tinted Ball Jars were among the refuse next to the cabin.

Unfortunately if you are using an app like All Trails and have the GPS track saved, and you take the Jones Pass Trail you begin to second guess yourself, as I did. Sometimes you can think that it’s just a mis-calibration of the GPS as your position is off by a couple of hundred feet from the GPS track. Unfortunately at the first major turn it became obvious I was either on a game trail along a ridge or not on my desired trail at all. I cut hard back east to course correct and quickly found myself on a game trail that petered out into an avalanche chute.

Bushwhacking

Clearly I had made a mistake, but just how badly of a mistake it was had yet to be seen. To say that I’m stubborn doesn’t quite encompass how much I didn’t want to lose elevation here. But my boots were having some difficulty as I picked lines that appeared to be game trails to cross the avalanche chute. Rocks rolled downhill as I dislodged them, and I spun around downed seasoned timber trying not to wrench an ankle. I kept looking at my GPS track hoping that if I kept enough elevation over the trail I’d eventually just see it. No dice, for 9/10ths of a mile of grueling downed timber and stacked elevation lines.

Soon though I was able to intercept the trail at a switchback and drop on to the singletrack I’d inadvertently avoided some several hundred yards above in the chute. From there the walking was easy, onward and upward.

What I didn’t notice however, as I marched onward, recovering from the feeling of being beaten by the avalanche chute was that I’d missed a switchback to Vasquez Peak, and the trail split in a weird way. Left to the Peak, right to the Pass. By the time I noticed on the GPS it was too late.

Vasquez Pass

Coming into the area of the pass itself began a series of snow fields that required some care to cross. Though I left early enough that I did very little post-holing, there were a few areas that I needed to dig in the side of my boot to get purchase. In a few more weeks those fields will likely be gone. The trail snaked through the valley, staying on a ridgeline giving a great view of the creek which had become a trickle, a mix between snow melt and a natural seep.

I passed a fire ring in the pass that might make for a windy overnight, but seemed like it might make a nice base camp for someone wishing to ptarmigan hunt the area inside the wilderness area. Protected by the imposing peaks on both sides and elevated from the spring it seems like you could carve out a little backcountry living for a couple of days chasing those mottled brown and white nerf footballs.

It seems almost needless to say, but the hike down was quite a bit easier. Recognizing my mistake on the way in meant that I was able to hike the Continental Divide Trail and all of it’s switchbacks back down to the truck while avoiding beetlekill, blow down, and a giant avalanche chute. Legs wobbly and lungs burning I made it back to the truck and flopped on the tailgate to take a break, but I couldn’t shake the feeling I just didn’t give the Wilderness Area it’s due.

Take 2

This is the first Wilderness Area I’ve returned to because I just didn’t feel the first hike did it justice. Looking at the map, at the top of the pass I was just barely in the Wilderness Area. That felt like cheating to me, and it didn’t expose me to the true nature of what we decided was worth protecting. I couldn’t leave well enough alone, so I decided to make my plan to go back.

A few weeks later I had a Friday free where I could escape the climbing temperatures in the Aurora and Denver area and drive out to the mountains again. I now knew where to park, and where to make the dog leg in the trail to ascend to Vasquez Peak itself. Looking at the map the Peak eponymous of the Wilderness Area was also just inside the wilderness boundary. No matter, I was going to do it anyway.

Hiking the switchbacks on the now seemingly familiar trail I quickly got into the zone. One foot in front of the other. Perhaps it had been the lack of stretching at the truck, or only drinking a shake for breakfast but things were going slower today. I was robotically looking to gain miles and elevation when suddenly crash! In the timbered area where beetle kill was being abated by the Forest Service at once I saw a head look at me, and then a rather large rump as a cinnamon colored black bear crashed away from me uphill and further into the bush. That did what the nearly full pot of coffee couldn’t do that morning. I was awake now, and hyper aware of my surroundings. Haunch to haunch the bear’s butt looked like it was four feet wide, and the first bear I’d seen in my Wilderness Area hikes.

Welcome to Mordor

I took the trail dogleg this time, away from Vasquez Pass to the Peak and in short order it looked like something out of a Grimm Fairy tale or Lord of the Rings. “Welcome to Mordor” was the first thought that passed through my head as the trees around me switched from conifers to deciduous trees that had all been killed by some sort of blight, surrounding the trail like a sort of ominous trellis of destruction.

From there was another trial to test my mettle. While it wasn’t technically tree line, the trees were stunted and as I gained elevation the boulder fields began. Oh the boulder fields. On this second trip to the Vasquez Peak Wilderness I had two things in mind. To summit the mountain and to scout for white tailed ptarmigan. While they aren’t the “devil birds” that chukar have been called, they certainly have given me fits the last two seasons.

I stopped to glass the boulder and talus fields as I rounded curves in the trail, heading ever skyward. Stopping to take some wildflower pictures I leaned over throwing the camera into portrait mode only to feel extremely lightheaded on standing up. I was over 12,000ft in elevation for the second time of the season. Sitting on my couch these long months trying to wait out a pandemic had not been kind to me, and I almost passed out.

I refueled and hydrated before trudging on. I still hadn’t summited the mountain and it was getting close to 9 in the morning. Elevation was slowing everything down, and what’s more, I’d missed my turn to the route I wanted to take up to the top. It wasn’t an “official” trail, but there were carins — something I wouldn’t see until my descent. I decided to take the westerly ridge up the peak, and almost made it. Both time and elevation took their toll on me.

A Route Less Chosen

The mountain though, took it’s pound of flesh. In my walking on the single track just after the boulder field I managed to catch a rock enough to somersault over a ridgeline. In an attempt to save myself from rolling off the mountain I initiated a truly disgraceful pirouette and twisted my ankle and skinned my leg fairly good. It was throbbing and sticky with blood underneath my somehow unscathed hiking pants.

I climbed and glassed up the western ridge, but soon I found I couldn’t climb any further. Just like in Byers Peak Wilderness I could either summit or look for birds, but probably not both. I stopped about 300 yards from the summit lightheaded, dehydrated, and sore. Much to my chagrin, still not inside the Wilderness Area boundary.

I used the recovery time to glass the entire mountain for birds, but I’m certain the few hawks that were using the updraft in thermals to hover over the talus fields had put most of them into hiding. I took an alternate route down the mountain, finding the original descent trail that was marked on my map. It involved a little glissading, or whatever the dirt version of butt scooting on loose soil is called in order to lose elevation.

Sore but satisfied with the adventure I trudged down the hill, meeting the first groups of hikers I’d seen all day — now approaching noon people were still on the ascent into the high country. While I usually caution against it, the sky was bluebird and completely cloudless. Vanquished by Vasquez yet again I had to go back to the truck and plan my third outing — the good news is that any other trail that touches the Vasquez Peak Wilderness is mild by comparison.

But… You Didn’t Finish!

I had to go back to Vasquez several more times this season, and will post an update when I finally Vanquish Vasquez.

Henderson Mine

You can’t talk about the Vasquez Peak Wilderness without talking about the Henderson Mine. The large superstructure looms above the valley floor, and the ventilation of the below ground molybdenum mine sounds like a jet engine on the tarmac. It sits between two large swathes of public land, and the mine maintains some of the roads going up to the Wilderness, as well as the trailhead parking lot. These are the marks of people who are happy to be in the area doing their work, and why not? In my experience the folks who work shop floors, logging operations, and miners are some of the most outdoorsy folks know. It’s a privilege to be able to work somewhere you can cast against trophy trout in Clear Creek on your lunch break, or take a quick hike in the Pike National Forest.

| Getting There From Denver hop on your 470 of choice (E or C) westbound, exiting onto I-70 towards Grand Junction. From there take Exit 232 to US-40W and stay on it for 11.8 miles. Take a left at CR202 Jones Pass Road, and at the entrance to the Henderson mine bear right onto the dirt road. From there it’s another 1/4 mile or thereabouts to the two dirt lots associated with the trail. In the winter it’s used for loading and unloading snowmobiles and in the summer largely for hikers venturing to the CDT. |

| Why am I doing this? I’m on a quest to hike, camp, hunt, or fish on all of Colorado’s federally designated Wilderness Areas. Check out all the articles here! |

[…] « Previous Story […]