So by now you’ve been utilizing mapping technologies to check public land boundaries, and probably for a doing little cyber scouting. But what about finding brand new places to hunt? Some of my favorite places to hunt are old abandoned homesteads deep on public land. There’s something about Ruffed Grouse that seem to love these places, once tamed but now wild. Wherever there’s an old foundation there is likely grouse nearby.

I’ve long hunted ruins of a farmstead that sits inside of a State Gamelands in Northwestern Pennsylvania. There’s remnants of stone foundations of a house, large barn, well, and perhaps a root cellar. Around those ruins there are apple trees, a sunken depression that is sometimes a pond, and overgrown shrubbery that always seem to produce grouse. I’m also aware of a parcel of land, roughly 100 acres, that never used to be part of State Game Lands property that was recently added to their holdings. I have my suspicions that the holdout was a family farm. Perhaps it stayed in the family because taxes in the area were low. I wonder… is there another set of ruins on that property or elsewhere?

Finding Your New Honeyhole

While I’m not giving up the details on my favorite spot to check for a grouse or two, I think there might be a new way to locate properties that doesn’t involve sitting for days at your local library. You’ve already figured out how to locate public land, and there’s plenty of resources to be able to do that. Heck, if you’re not sure about huntable land in your state, we’ve got you covered.

LI-What?

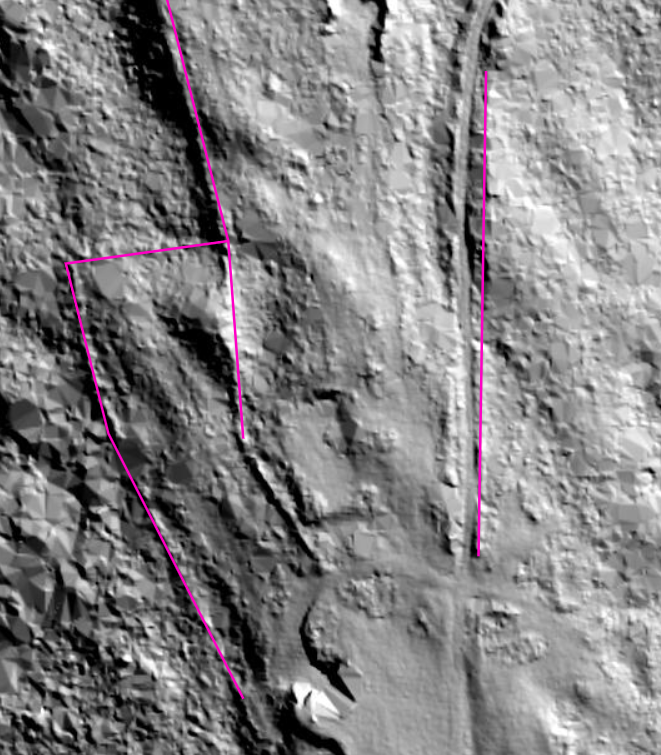

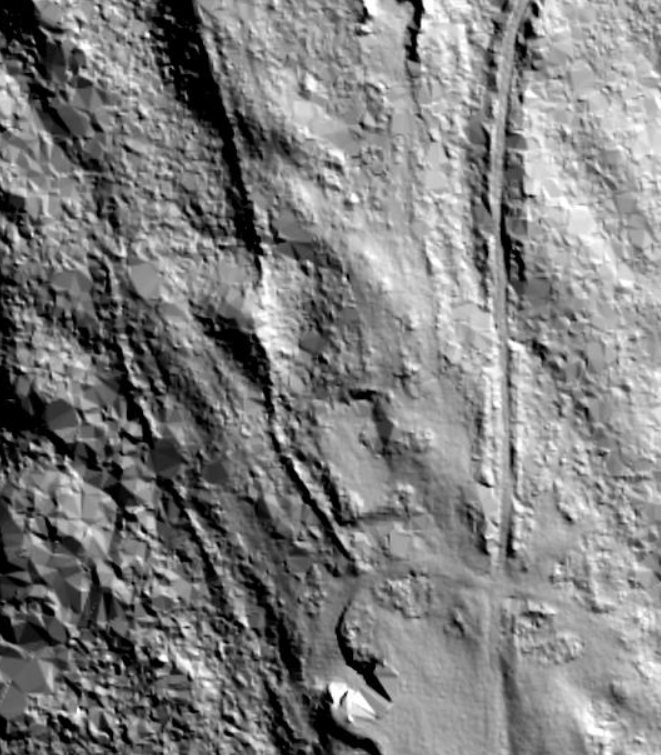

LIDAR stands for Light Detection and Ranging. It’s a remote sensing technology that’s used to take a deeper look at the surface of the earth. It’s used to map terrain both from space as well as from fixed wing aircraft. Interestingly it sees through the dense canopy of the trees and creates a map of elevation based on the ground. It can also be used to measure vegetation density and height, which is a topic for another article.

We’re interested in topographic LIDAR that uses a near infrared laser, scanner, and precision GPS to map the land. It can effectively delete the canopy of trees hiding structures below. When two passes of LIDAR are taken from a low flying fixed wing air craft the images can be combined for a 3D hillshade style image that gives depth to the observations. Even with a plane flying at about 180 miles per hour the images can be very detailed.

If you’ve been following our Hunting Maps for Lunatics series you’ll know that there’s Geographic Information Systems (GIS) layers for just about everything. LIDAR is no different, add it to your mapping repertoire and you might be surprised. You may just find something you weren’t even looking for in the woods.

Indiana Jones with a Laser

I first learned about the applications of LIDAR several years ago when I read about a researcher in the United States stumbling upon Native American burial mounds. Since then more articles have popped up analyzing the Mayan civilizations finding more than 60,000 home sites. The data proves that the culture was indeed more expansive than previously thought. The technology has also been used to analyze the jungles outside of the famous Angkor Wat temples in Cambodia where even though most of the buildings were built from wood the disturbed dirt mounds remain. The dirt mounds used as foundations or building pads give away previously unknown archaeological sites.

LIDAR has revolutionized archaeology even in the last decade, providing a birds eye view of civilizations that have been gone for hundreds or thousands of years. Every year sensors are getting better. Even though data might not exist in your area, forward thinking companies are already seeking to scan the globe. The data is valuable.

Science, Applied in Your Back Yard

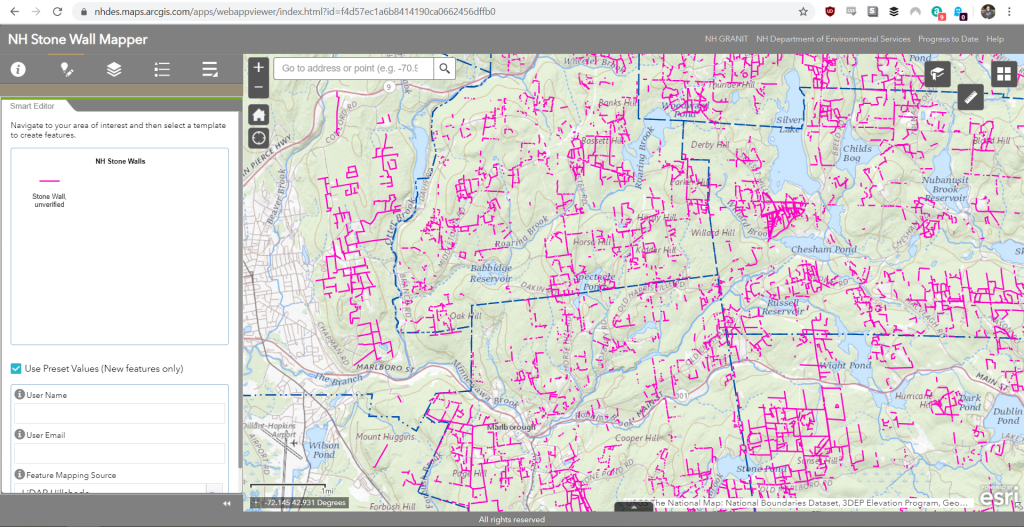

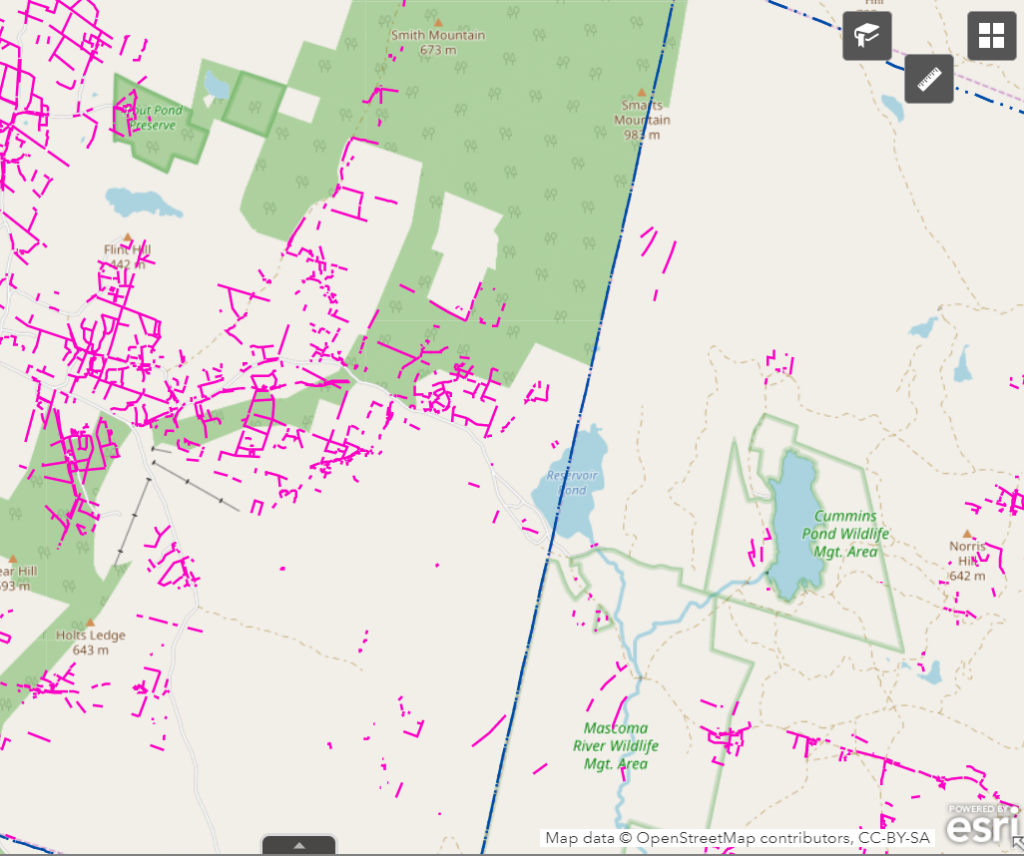

While it seems like science fiction, LIDAR data has already been used to map old stone walls left in the Northeastern United States through University of New Hampshire’s Stone Walls Project. The project is seeking to map out old stone walls by crowd sourcing imagery analysis to the general public. Anyone in John Q Public can look at the map, analyze it for a straight wall and mark it. When it’s marked it becomes light pink on the map as an unverified stone wall.

Stonewalled

So what’s the deal with all the walls anyway? Settlers first came to farm the land of the new world. Unfortunately for them there was tree cover and a massive glacial deposits of rocks. Upwards of seventy percent of the forests were logged. Rocks removed and piled into fence lines because they just didn’t have anywhere else to put them. Upon each large rain storm or winter from heave thaw there were more rocks to add to the growing piles. Piles became fences marking ownership boundaries between properties or within properties for animal stalls.

For me, these walls indicate ruins and structure. Much like fish are attracted to structure underwater to live in, grouse are likewise attracted to edge habitat. Not much grows on a large rock wall, so there are gaps beside and around. These walls were once demarcation lines for property, separating farmhouse from field. So on one side may well be an orchard of apples gone feral, and the other a former livestock paddock.

Crowdsourcing Coverts

Since the maps are analyzed by the public there are false positives. Often the unnaturally straight lines can be roads or other old man made objects. However, when viewed through the lens of hunting — all of these things can be of interest to us. Grouse and other game birds love edge habitat. Even old bulldozer or logging roads are beneficial to know about in the grand scheme of things. But if you find the 90 degree angles of an old rock wall fence forming boundaries of an old unmolested farmstead you might be in for a real treat. Maybe some apple trees went wild, maybe there’s remnants of a windbreak between fields. The prospects for hunting and exploring are many.

So that’s New Hampshire where some of the work is already done. But stone fences should only be where people are, right? Well during the course of the last several hundred years the fences generally withstood the test of time. Even though the land has transferred many, many times the likelihood of the walls being destroyed is slim. That cool formation above by the way? It’s on public land. That’s the trick. Cross referencing maps, LIDAR, and land ownership. Sound like too much work? Well, that’s the type of obsession that just might give you the edge on other hunters.

What’s Next?

In our next article we’ll talk about sourcing, using, and analyzing the data to see if we can’t find some new places to hunt based on our access to publicly available LIDAR data.

Resources

- The Geology of Colonial New England Stone Walls

- New England Is Crisscrossed With Thousands of Miles of Stone Walls

- What is LIDAR?

- Seeing the Forest Through the Trees with a New LiDAR System

- NH Stone Wall Mapper

- Scientists Use LiDAR to Discover Massive Lost Mayan City

- Borgring: the discovery of a Viking Age ring fortress

- Looking at LiDAR to Map Stone Walls [PDF]

- Exclusive: Laser Scans Reveal Maya “Megalopolis” Below Guatemalan Jungle

- Stone walls can be found via LIDAR from above, crowd-sourcing from below

- Laser Scans Reveal Massive Khmer Cities Hidden in the Cambodian Jungle

[…] « Previous Story […]